“This is a hard time to start a magazine. The country shaking like an old drunk. Who knows he has to give up the hoosh. Does not provide a climate of reason and ease that magazines thrive on. There is a recession.Magazines are collapsing left and right,” wrote Roger Black in his role as Editor of a magazine called AMERIKA in 1970.

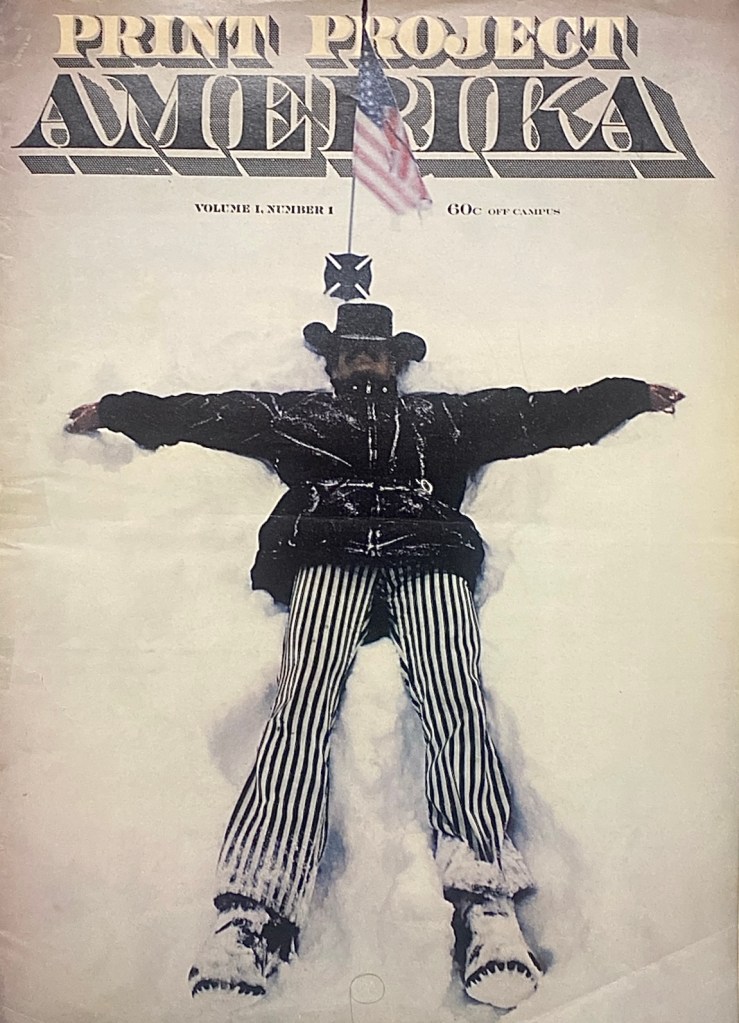

Mr. Black was a student at the University of Chicago and editor of the students’ newspaper, The Maroon. AMERIKA was forced to change its name after the dummy issue was published and the first and only issue published was called PRINT PROJECT AMERIKA.

I reached out to Mr. Black to talk about the story of AMERIKA and to get an update on what he is up to these days. He told me that he’s “back actually doing a publication. And this is an urgent time for magazines and newspapers. We must find a way of keeping them going, keeping them independent.”

In fact, Roger Black wrote this week on his Facebook page under the heading “ROGER BLACK’S FAREWELL TOUR?” Join me at Big Bend Sentinel, where a team of innovative journalists is redefining local news. We’re testing two old ideas. In the video (that accompanied the post) watch for the key words: “fact” and “art.”

Mr. Black continued, “I started this tour in 1973 as art director of LA (1973). Now, as acting Art Director and non-profit chair, I’m back to weekly newspapers! The real work is done by a small energetic band of editors led by Rob D’Amico, Sam Karas, Mary Etherington, and Ariele Gentiles.”

He adds, “Can weekly newspapers survive and flourish? Can we hold onto local journalism?”

I reached out to Mr. Black to ask him about his original work on newspapers and magazines. I was mainly interested in the very first magazine, “AMERIKA” he edited while still a student at the university. Needless to say, he is a wealth of information and he has left his thumb print on many national and regional publication throughout his career. I hope you will enjoy this lightly edited conversation with a person who for years I called “a genius creative art director.”

Samir Husni: You ask Chat GPT about Roger Black and it tells you, “Very influential in magazine and newspaper design,” but no mention that you were an editor of a magazine back in 1970 while you were still a student at the University of Chicago.

Roger Black: Yes.

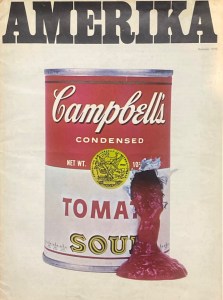

Samir Husni: And the magazine was called America with a K: AMERIKA

Roger Black: Well, that was the dummy. Later, it was PRINT PROJECT AMERIKA. There were only the dummy issue and the one and only first issue.

Samir Husni: So, tell me about your journey with AMERIKA.

Roger Black: AMERIKA was envisioned as Parade magazine (The Sunday newspaper supplement) for student newspapers.

In 1968, I was the editor of the Maroon, the student paper of the college at the University of Chicago. I must tell you, that was a very good year to be a student editor. And particularly in Chicago.

We had a lot of news. It was a big time for change. We started putting out a weekly magazine called Gray City Journal, which ultimately became its own publication.

So we started thinking that many student papers don’t have that kind of content. Harvard, Yale, and other elite schools do.

But in terms of magazine style, both entertainment and serious stuff, photojournalism and drawings, they didn’t really exist. If you go back and look at the 1960s’ student newspapers they were pretty dry.

A guy in the business school at the university, named Mark Brawerman, who is from California, came up with the idea.

A very sharp guy who just started school. He didn’t really have any business experience.

He thought that we could do this. One of the things that he did, and with my involvement, I thought it was a good idea, too, he started writing all the student newspaper editors and publishers saying, we have this idea.

Would you be interested in taking it? And we’re going to print a prototype, and you can decide. That was the reason for the prototype; we had to get the circulation.

I was interested in design. I had started doing some publication work before I got to college. I had a wonderful teacher named Robert Gothard, a famous typographer, who did student, alumni magazines, and other publications for universities and colleges and did other things, too. He was a great designer.

So, I got interested. He was the first art director of Print magazine, for example. I was really interested in magazines from really as a young kid. My mother worked for magazines.

We had written all these people, and we got enough responses that if we could print 200,000, we could have distributed them.

So I started working on the prototype. And it’s funny because my girlfriend at the time is listed as the art director. I don’t even remember her name now.

There you go. The prototype cover came from Kent State. It was from an art student there who did this kind of Andy Warhol homage after the Kent State shooting. And there’s more stuff of that inside. Anyway, I thought I could be a designer.

I looked at a lot of magazines. How hard can it be? So, I did this issue, this prototype. And by some wild set of coincidences, Sam Antupit, who is a great art director, the art director of Esquire at that time.

George Lewis did the covers, but he did the inside. And it was beautiful. He was doing a special issue of Print Magazine about magazines.

And he put this in a box called Hopeful Upstarts. We realized we were going to leave Chicago and move operation to New York. So, I got to New York and I looked him up.

And we had gotten some funding. We were starting to sell ads. But I couldn’t find an art director.

That was the funny thing. There weren’t a lot of people, if you think about it, Rolling Stone and New York Magazine only started in 1967. And before that, there were art directors at Esquire or at Town and Country or the fashion magazines, and Holiday magazine.

There were certain kind of visual magazines that had art directors. But National Geographic didn’t have an art director. Life Magazine didn’t have an art director.

It was not really one of those job descriptions that people, their mom said, you can be an art director. No one, no one really was thinking about that. And I couldn’t find any.

But Sam had this fantastic studio on, I’m going to say, East 52nd Street in a brownstone building. Later, the previous Citicorp Village was built there. But he was doing a bunch of different magazines out of the studio or doing designs, and redesigns.

He had a famous magazine artist, Richard Hess, who was his partner in that. So, it was called Hess and Antupit.

It was the name of the studio. And they were on the top floor. I was totally blown away how great it all was.

He did have student aides from SVA or Pratt or Cooper Union students working part time or as interns for him. What he couldn’t really recommend any other kids to be art directors. I finally came back and asked him if he would do it.

And by some miracle he said yes. And agreed to our price, which included all the type setting, all the illustrations and photos, the whole art project. He said he would do it for a fixed price.

I probably lost my shirt on it. He took over in that first real estate number one. It was really the designer’s Hess and Antupit.

I got to be the editor. So that was fun.

Samir Husni: The dummy issue was called AMERIKA, and the first issue PRINT PROJECT AMERIKA, why did you change the name?

Roger Black: I’ll tell you the story why we changed the name.

We got a letter from the Catholic Church. They sent us an official letter saying that they have a magazine called America and we have the trademark, so you can’t use America even with changing the C to a K.

Of course, I knew even at age 20 that you can’t trademark a place name. You can’t put a trademark on America. So I wrote back saying, you can’t trademark a place name.

So, I’m ignoring their letter. They wrote back and said, well, how many lawyers do you have? Basically, I said, these people are going to give us a hard time. I’m going to just add a qualifier.

We added the phrase PRINT PROJECT AMERIKA. We made it more experimental, new media feeling.

Samir Husni: The State Department didn’t send you a letter saying we have a magazine aimed to the Soviet Union called America.

Roger Black: Well, their magazine was only circulating in Russia. And we weren’t going to Russia. They are not allowed to distribute it here.

Samir Husni: In this digital age, where do you see print role?

Roger Black: Print magazines had a very good run. I like to say it was a hundred-year run. If you look at the magazines, like the late 19th century, magazines that started running art, photo engraving had come in.

They were impressive. And then you had with the invention, of rotary presses and linotype typesetting and all that. Magazines followed the newspapers in increasing press runs.

So you had the concept of mass magazines. That whole business model kept morphing. Everyone forgets about this, you know, like in 1995, the commercial web appeared and everybody said, oh, everything’s over.

But I don’t think the commercial web was much more of a kick in the head than the television. And before that, there was a similar abrupt change with radio. The idea that entertainment could just sit in your chair and not have to think and just listen.

Magazines like The Saturday Evening Post were really hurt by that. Because that was their position, at home after they were reading entertaining stuff. But they survived and they adapted.

I think that the biggest challenge for a contemporary magazine, and that also includes online, is the attention span problem and the way that the kind of addiction to the constant scroll, just going vertically with dozens of different things that you’re barely aware of what it is. You stop on a cat or whatever you want to look at.

That has changed dramatically in the last 10 years. We didn’t even know about TikTok 10 years ago. And Facebook seems for people my age now.

All that keeps morphing. Instagram had its moment in the sun. And everything, everything is always moving. My feeling is that print offers a new kind of respite for that.

In the way that radio seemed like a respite for reading. Print, going back to reading, is a relief from that addictive scrolling that everyone’s doing. Or just that very short attention span, you look at one thing, you look at another thing, you look at another thing.

That kind of short attention span gets tiresome after a while. And why can’t I say that with any confidence? It’s because the long form media, like books or movies, are blasting ahead fun. I mean, movie says, the movie, the Hollywood studio business is once again in convulsions. With every year, there’s a headline that says, Hollywood is no longer the same. It will never be the same.

We don’t recognize it anymore. And they’ve been saying that since about 1920 since talkies came in. So that long form sitting in a movie theater or watching it on Netflix is a very compelling experience.

And people enjoy it. It’s still, there is a business model in the same way that music kind of changes business model from the time of the record business. Movies are too, but also books.

It’s very interesting to me to see things like the eBooks for the digital side, but also bookstores are coming back. There are new bookstores everywhere. And there are very niche bookstores.

Bookstores about cooking or bookstores about architecture. All over the place. It’s fairly like Marfa, Texas, where I am right now, it’s just a few thousand people, right? It has an extremely good bookstore that also has a quite a good art collection.

Now, Marfa may be a special town, they just finished a new library or a big addition to this little library in Marathon, Texas. Population 400. And every time I’ve been by it, it’s full.

A lot of kids. Why is that? Because there’s something very pleasant about holding a book and reading it. And getting it, one of the advantages that books have and movies have over the endless internet is that you finish the book.

I’ve read the magazine. I’m done. I finished The New Yorker.

Almost nobody can say that online. There is a real feeling of accomplishment. And of course, The New Yorker’s secret that Howard Gossage, the advertising man, pointed out when he was doing their advertising.

The cartoons in The New Yorker are the guilt reliever. Because you can go, page all the way through, get a few chuckles. You might read a talk piece or one or two other things.

And then you sit the magazine down and somebody says, and you mentioned something that you saw in The New Yorker. I read it in The New Yorker. I read The New Yorker every week.

That’s a definite feeling of accomplishment. From a psychological point of view, there is satisfaction that comes from the phenomenon of the edition. This is a magazine.

This is the September issue of our magazine. Or this week’s magazine. Whatever.

And the same thing. You get to feel like you finished it. You go through it.

The online newspapers, you never finish. The digital crowd is very surprised that people like the PDF replicas of newspapers. Like The Dallas Morning News now presents that first.

If you go to their website, you get the replica first. Then you get the actual website. Because people know how that navigates.

They know where their stuff is. Everything’s in a familiar place. And things like PressReader made it increasingly easy to read on different devices.

The feeling about sessions, session time, completing an edition, very important. I think that magazines, in the same way that I think anthology, television like 60 Minutes will go on despite everything else. Now we still must work on the business model.

The numbers are much smaller than they used to be. We’re not doing mass magazine. But I think that quite a few people, we see people getting in and surviving.

And it’s delightful.

Samir Husni: Mr. Black, if someone comes to you and says, I want to start a new magazine, what do you tell them?

Roger Black: I really ask them, who’s your reader? I think it all starts with the reader.

Who is it you’re trying to talk to? Have you talked to them? You communicate with them. And I think that’s the way that we all got in the media have gotten in trouble over the years, is that we think that we’re the media. And it’s a two-way thing.

Reading is interactive. And I continue to find, maybe it’s because of my extreme age, I find reading the most effective kind of communication. It’s faster, it’s cheaper, and it’s inexpensive, as opposed to a video that you do on TikTok or YouTube.

That’s an effort. It’s a production. Maybe we don’t have a TV station like we used to.

And we’re relying a lot on Apple and the others to fix our video for us. But I think that having a group of people just writing, taking pictures and putting them together into a magazine, is very low cost compared to what the big guys are trying to do. And I think you can, if you make it good.

If you connect with the reader, it can work. And it doesn’t have to be high art. It doesn’t have to be the kind of level of journalism you’d expect in The New York Times or something else.

But if it can be good and readable, and is hitting a chord that people like, I think you can make it. One example you mentioned, Arena, the Santa Fe magazine, which is two old, French, encrusted print guys. One, John Miller, worked with me.

Owen Lipstein, somewhat controversial publisher from New York, who was the publisher of Smart Magazine, which I did in the late 90s with Terry McDonnell, only 13 issues ever published. Anyway, they got the idea of doing a big fat real estate magazine in Santa Fe, which of course, people in Marfa would say that Santa Fe is a real concoction of the real estate salespeople, which it may or may not be. But what they did to get the content, because they didn’t have a huge budget, and none of this stuff, no one is paying what Vanity Fair is paying.

I don’t think even Vanity Fair’s paying what they used to pay. But what John Miller, the editor there, and designer, did was to just do a lot of interviews. He had video, and some of the interviews were trimmed to just be the answers.

It was like a first-person article. Sometimes they would have a lot of pictures of their home, or they would go there. Sometimes it was just pick up what they could provide, the decorator, the designers, pictures of the house or whatever, or their potters, and they had stuff on their website.

Just thinking about it carefully and making it interesting with interesting people.

Basically, it’s all about the people in magazines. So you start with the reader, but then you give them stories about people to read.

That’s basically the core of every good magazine.

Samir Husni: Before I ask you my typical two last questions, is there any question I failed to ask you you’d like me to ask?

Roger Black: I sort of expected you to say, why are you still doing this? Which is funny, I don’t know what else I would do. It’s like somebody says, why do you have this place in Texas out in the desert? And my answer is, I can’t think of anything, any other place I’d rather be.

I can’t think of anything else I would rather do than try to work with typography. We have Type Network, I’m chairman of Type Network, and we’re doing a wonderful collaboration with 100, more than 100 type designers and type founders with special custom design projects. Some of it is consulting, and some of it is type design.

I’m not a type designer, but I can connect them to the market. It’s a very small operation, but quite fun. I want to keep working.

My father worked till he was 80. And then, even later, he said, I never should have quit. So, the next question is, what are you doing now? As well as Type Network, I’ve come out to Marfa, and I’ve taken over by starting a new non-profit with Don Gardner from Austin, and Gonzalo Garcia Bautista from Mexico City.

We have started a non-profit, and we are now publishing this paper, which you can go to at BigBenSentinel.com. You can join and get the PDF, or we’ll mail it to you. For 60 bucks, we’ll mail it to you.

Folks, that price is going up, so act now.

Samir Husni: If I come unannounced to your house…

Roger Black: In Marfa, now? Well, it’s a marathon. I also hang out in Florida. We’re still repairing from the hurricane last year.

And I have an apartment with my husband in Oslo, Norway. So, I kind of am nicely balanced.

Samir Husni: So, if I come unannounced one evening, what do I catch Roger Black doing to rewind from a busy day?

Roger Black: Reading. I’m still old-fashioned.

Samir Husni: And what keeps you up at night?

Roger Black: I don’t stay up at night. I am a great sleeper.

I don’t know why. I go to bed early. I go to bed by 11 or so.

In the old days, I’d stay up late. My peace of mind results from, as you get older, you realize you must let things go and become balanced, or you’re always anxious. The other thing that helps me, has helped me in my whole life, is I have a colossally developed ego.

It doesn’t occur to me until years later that I could be wrong. It’s like later people point out, that was a complete disaster. And I say you’re right.

I was completely unaware of that at the time. And I still, you know, it’s like I tried to do that thing, Screensaver, I thought we could do a technology solution for reading digitally. And it turned out that it didn’t work beautifully.

It turned out that the publishers didn’t have a business model for that. So, I do find myself waking up sometimes and thinking about those things. But I go right back to sleep.

I’m not what you’d call a troubled old man.

Samir Husni: Thank you. Take care. Have a great day.